Judges Chapter 1

Title and Canonical Setting

The English title “Judges” is derived from the Latin Liber Judicum, following the Septuagint title Kritai. The Hebrew title is שֹׁפְטִים (Shophetim), meaning “judges” or “rulers.” These judges were not primarily judicial figures as we think of today, but rather charismatic military leaders who functioned as deliverers, governors, and occasionally prophets. Their role was to restore order in times of national rebellion and foreign oppression.

Judges is the seventh book in the Old Testament canon and the second historical book following Joshua. It is part of the section of Scripture known as the Former Prophets in the Hebrew Bible and is considered historical narrative in the English arrangement. It prepares the way for the monarchy introduced in 1 Samuel.

Authorship and Date of Writing

The book does not identify its human author. Jewish tradition, dating back to the Babylonian Talmud (Baba Bathra 14b), credits Samuel as the most likely author. This tradition is supported by several factors:

The refrain “In those days there was no king in Israel” (Judges 17:6; 18:1; 19:1; 21:25) suggests the monarchy had begun or was expected.

The moral and social anarchy described seems to prepare the reader for the demand for a king in 1 Samuel 8.

Samuel, as the last judge and prophet before the monarchy, would be in the best position to compile this national and spiritual history.

The date of composition is likely between 1050 and 1000 B.C., during the early years of Saul’s reign or possibly under David. The events themselves span roughly 1380 to 1050 B.C., covering three centuries of Israel’s early national life in the Promised Land.

Historical Background

The Book of Judges follows the death of Joshua and the elders who outlived him (Judges 2:7–10). After the initial victories in Canaan, the tribes of Israel failed to complete the conquest. God had commanded in Deuteronomy 7:2, “...you shall conquer them and utterly destroy them. You shall make no covenant with them nor show mercy to them,” but Israel compromised and coexisted with Canaanite idolaters.

This disobedience set the stage for a national cycle of sin:

“When all that generation had been gathered to their fathers, another generation arose after them who did not know the LORD nor the work which He had done for Israel.”

— Judges 2:10, New King James Version

The tribes became increasingly idolatrous, morally corrupt, and politically unstable, leading God to discipline them by raising foreign oppressors. In response to their cries, He raised up judges to deliver them.

Literary Structure

The book follows a chiastic and cyclical narrative form, and is often divided into three major sections:

Prologue: Israel’s Failure and Apostasy (Chapters 1–2)

Incomplete conquest

Spiritual compromise

Introduction to the cycle of sin

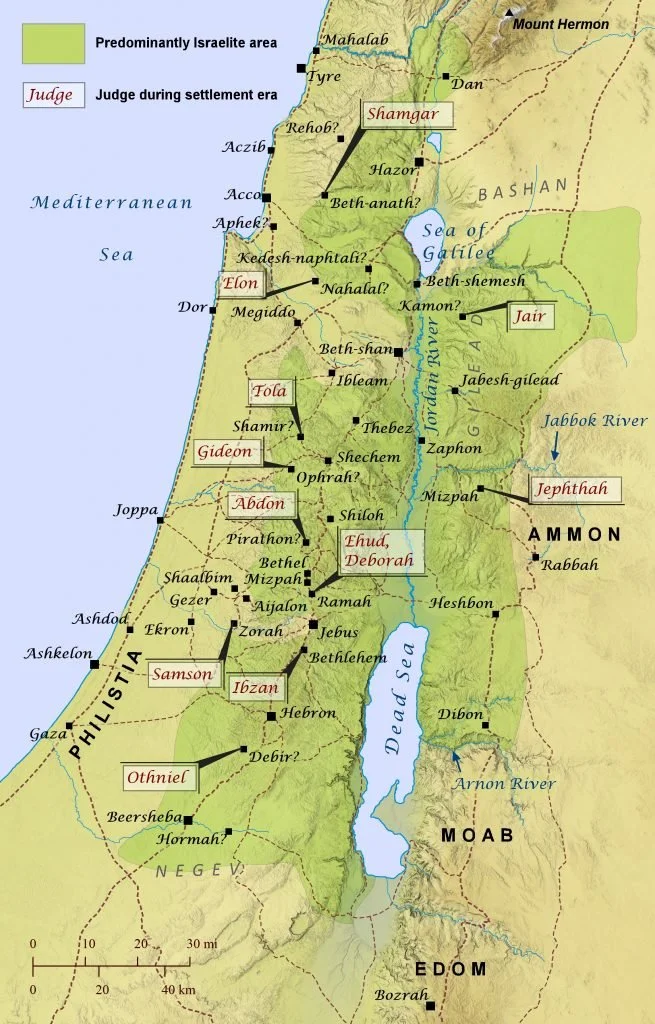

Cycles of the Judges (Chapters 3–16)

6 Major judges: Othniel, Ehud, Deborah (with Barak), Gideon, Jephthah, Samson

6 Minor judges: Shamgar, Tola, Jair, Ibzan, Elon, Abdon

Repeated pattern: sin → slavery → supplication → salvation → silence → relapse

Appendix: National Corruption and Civil War (Chapters 17–21)

Religious corruption: Micah’s idol and the Danites

Moral depravity: the Levite’s concubine and the war with Benjamin

Purpose of the Book

The Book of Judges was written to:

Demonstrate the consequences of Israel’s covenant unfaithfulness

Illustrate the Lord’s righteous judgment and covenant mercy

Show the spiritual chaos of a nation without godly leadership

Warn against the dangers of moral relativism and theological compromise

Point forward to the need for a righteous King who would deliver Israel permanently

Theological Themes

1. The Kingship of God

God was Israel’s King (Exodus 15:18; Deuteronomy 33:5), and Judges reveals what happens when that divine rule is rejected. The repeated phrase:

“In those days there was no king in Israel; everyone did what was right in his own eyes.”

— Judges 21:25, New King James Version

…emphasizes Israel’s abandonment of theocracy in favor of self-rule. The absence of leadership leads to moral, civil, and spiritual collapse.

2. The Cycle of Sin and Deliverance

Each cycle includes:

Rebellion: “Then the children of Israel did evil in the sight of the LORD…” (Judges 3:7)

Retribution: “Therefore the anger of the LORD was hot against Israel…” (Judges 2:14)

Repentance: “And when the children of Israel cried out to the LORD…” (Judges 3:9)

Rescue: “The LORD raised up a deliverer…” (Judges 3:15)

Rest: “So the land had rest for forty years…” (Judges 3:11)

3. God’s Providential Mercy and Sovereignty

Despite repeated rebellion, God remains faithful to His covenant and His people. He raises deliverers by His Spirit and acts out of compassion:

“And when the LORD raised up judges for them, the LORD was with the judge and delivered them out of the hand of their enemies all the days of the judge...”

— Judges 2:18, New King James Version

4. The Consequences of Compromise

The failure to obey God’s commands regarding pagan nations (Deuteronomy 7:1–5) led to spiritual defilement, foreign oppression, and eventual civil war.

“They did not drive out the Canaanites… but they dwelt among the Canaanites and took their daughters to be their wives…”

— Judges 3:5–6, New King James Version

Christological and Prophetic Significance

Although the book does not explicitly mention the Messiah, it contains strong typological and prophetic elements:

The judges prefigure Christ as deliverers, though each is flawed. The final Judge must be without sin.

The Angel of the LORD, who appears to Gideon and to Samson’s parents, is best understood as a pre-incarnate appearance of Christ.

The repeated failure of Israel under human leadership anticipates the need for a divine King—fulfilled in Jesus Christ.

“For the LORD is our Judge, the LORD is our Lawgiver, the LORD is our King; He will save us.”

— Isaiah 33:22, New King James Version

Relevance for Today

The Book of Judges reads like a warning to every generation:

When a nation forgets God’s Word, it drifts into darkness.

When families fail to disciple their children, apostasy multiplies.

When leaders fail to fear God, lawlessness fills the vacuum.

When truth is traded for autonomy, society collapses.

The final verse is not just a summary but a spiritual diagnosis:

“In those days there was no king in Israel; everyone did what was right in his own eyes.”

— Judges 21:25, New King James Version

This is not liberty—but anarchy. And this is not ancient only—it is our time.

Conclusion

The Book of Judges is a theological tragedy, a record of national decline under covenant neglect. It reveals the peril of partial obedience, the ugliness of sin, and the glory of God's mercy. The longing for righteous leadership is ultimately fulfilled not in Samson, Gideon, or Jephthah, but in the Lord Jesus Christ, the perfect Judge and eternal King.

“He will judge the world in righteousness, and the peoples with equity.”

— Psalm 98:9, New King James Version

Victory and Defeat in the Promised Land

Judges 1:1–2

Expositional Commentary

1. After the Death of Joshua (Judges 1:1a)

“Now after the death of Joshua…”

— Judges 1:1a, New King James Version

The Book of Judges opens at a decisive transitional moment. The death of Joshua marked the end of centralized, God-ordained leadership over the covenant nation. Moses had led Israel out of bondage in Egypt, and Joshua had led them into the Promised Land. But now there was no divinely appointed leader over the nation. There was no king, no prophet, no Moses, no Joshua. What remained was the Law of God and the presence of God among them—but without human leadership, the people were tested in their faith and obedience.

The absence of Joshua exposed a leadership vacuum, which would become a theme in the book. Unlike Moses, Joshua had not appointed a national successor. Thus, Judges begins at a fragile moment—a generation unprepared, without godly leadership, surrounded by pagan cultures, and burdened with unfinished obedience.

“Now after the death of Joshua…” — This phrase carries weight, for it reminds the reader that no human leader, no matter how great, is irreplaceable. The people of God must ultimately learn to live by faith in God's Word, not merely by the influence of their human leaders.

The challenge in this moment was to cultivate direct dependence upon the Lord. Without centralized authority, every tribe and every household needed to embrace God’s covenant individually and corporately. Israel was being tested to see if their obedience would continue when the visible hand of leadership was removed.

2. Israel Seeks the LORD (Judges 1:1b–2)

“It came to pass that the children of Israel asked the LORD, saying, ‘Who shall be first to go up for us against the Canaanites to fight against them?’ And the LORD said, ‘Judah shall go up. Indeed I have delivered the land into his hand.’”

— Judges 1:1b–2, New King James Version

Despite the leadership vacuum, Israel began well. They sought the LORD for guidance—an act that reflected humility and proper dependence. The question they asked was not “Should we fight?” but “Who should go first?” The conquest of Canaan had been commanded already. Their responsibility was to continue the work Joshua began and to trust that God would fulfill His promise as each tribe stepped forward in faith.

“Who shall go up for us...?” — This inquiry shows a unified national intention, even if it would later break down. It reflects a respect for divine authority, as Israel still sought the will of the LORD concerning tribal initiative.

God’s response is specific:

“Judah shall go up. Indeed I have delivered the land into his hand.”

— Judges 1:2, New King James Version

This divine selection is significant. The tribe of Judah is preeminent, consistent with Genesis 49:10, where the scepter would not depart from Judah. Though the monarchy had not yet begun, the tribe of Judah was already being positioned as the leading tribe of Israel. God's choice had both practical and prophetic implications.

Practical Reasoning

Judah was the largest and strongest tribe (Numbers 1:27).

Militarily, their strength was strategically suited to lead.

Judah had already demonstrated leadership in the wilderness (Numbers 10:14).

Prophetic Foreshadowing

The Messiah would come from Judah (Genesis 49:10; Hebrews 7:14).

The kingship of David would rise from Judah (2 Samuel 2:4; Matthew 1:3–6).

“Indeed I have delivered the land into his hand.” — The verb tense is prophetic perfect, meaning the victory is certain though not yet complete. God speaks of the battle as already won. It is a call to trust and act, not merely to hope and wait. Judah must rise and possess what God had already granted.

Doctrinal and Practical Application

Spiritual leadership must always point to God, not itself. When Joshua died, Israel had to determine whether their faith was in a man or in the covenant God who raised him up.

Godly beginnings require godly follow-through. Israel began well by seeking the Lord—but this will be contrasted with later chapters where they act independently and compromise with idolatry.

Divine direction precedes victory. Israel’s success depended not on numerical strength or military strategy, but on seeking God's will and obeying it in faith. When they did, He responded with clarity and assurance.

Judah's leadership foreshadows Christ’s kingship. God’s command that Judah take the lead points ahead to the Lion of the tribe of Judah (Revelation 5:5), the only One who can fully conquer sin and rule in righteousness.

Closing Summary of 1:1–2

These first verses set the tone for the book of Judges: a people standing at a crossroads between obedient faith and compromising disobedience. The death of Joshua tested the nation’s spiritual maturity. Their decision to seek the LORD shows a moment of clarity, and God's response to send Judah reminds us that God has not left His people without direction. Yet as the book unfolds, it will become painfully clear that initial obedience is no guarantee of lasting faithfulness.

“So I say to you, ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you.”

— Luke 11:9, New King James Version

Judah and Simeon Defeat Adoni-Bezek

Judges 1:3–7

Expositional Commentary

3. Judah Partners with Simeon and Defeats Bezek (Judges 1:3–7)

“So Judah said to Simeon his brother, ‘Come up with me to my allotted territory, that we may fight against the Canaanites; and I will likewise go with you to your allotted territory.’ And Simeon went with him. Then Judah went up, and the LORD delivered the Canaanites and the Perizzites into their hand; and they killed ten thousand men at Bezek. And they found Adoni-Bezek in Bezek, and fought against him; and they defeated the Canaanites and the Perizzites. Then Adoni-Bezek fled, and they pursued him and caught him and cut off his thumbs and big toes. And Adoni-Bezek said, ‘Seventy kings with their thumbs and big toes cut off used to gather scraps under my table; as I have done, so God has repaid me.’ Then they brought him to Jerusalem, and there he died.”

— Judges 1:3–7, New King James Version

A. Cooperation Among the Tribes (v. 3)

“So Judah said to Simeon his brother…”

The tribe of Judah initiates a strategic and spiritual partnership with Simeon, its closest kin (cf. Genesis 29:33–35). Simeon’s allotted territory was embedded within Judah’s tribal inheritance (cf. Joshua 19:1–9), and thus their cooperation reflects wisdom and unity. This tribal alliance models how God’s people are meant to function as interdependent members of one body, advancing His will in shared labor and shared victory.

The principle of mutual assistance between these two tribes is an example of how the body of Christ is to function in the New Covenant (cf. 1 Corinthians 12:12–27). Each part does its share for the benefit of the whole.

“I will likewise go with you…” — Judah’s invitation is reciprocal, not exploitative. The mission is mutual, the victory is shared.

B. Divine Victory Through Obedience and Unity (v. 4)

“Then Judah went up, and the LORD delivered the Canaanites and the Perizzites into their hand…”

The LORD’s role in the victory is emphasized. The victory is not attributed to Judah’s military strength or strategic alliances but to divine intervention in response to obedience. This is a core theme in Judges: When Israel seeks the LORD and obeys Him, victory follows.

The Perizzites are a recurring Canaanite people group, often mentioned alongside the Amorites and Hittites (cf. Genesis 15:20; Exodus 3:8). The Canaanites, representing entrenched idolatry and cultural wickedness, serve as a picture of the spiritual strongholds that must be conquered by faith and obedience.

“They killed ten thousand men at Bezek…” — The scale of the victory demonstrates that obedient partnership and divine favor yield overwhelming success. Bezek was located in the northern hill country, well outside of Judah's own territory—indicating that Israel was still fighting collectively, not just tribally.

C. The Capture and Maiming of Adoni-Bezek (vv. 5–6)

“They found Adoni-Bezek… and they defeated the Canaanites and the Perizzites… they pursued him and caught him and cut off his thumbs and big toes.”

Adoni-Bezek, meaning “Lord of Lightning,” likely bore a name meant to inspire dread. Yet even the most fearsome of earthly lords is no match for the power of the LORD when His people walk in obedience.

The word “found” implies hostile engagement, not accidental discovery. This was a direct and purposeful confrontation. The cutting off of thumbs and big toes, while shocking to modern readers, was a form of military incapacitation. It rendered a warrior unable to grasp weapons or maintain balance in battle. Thus, it served as both punishment and permanent disarmament.

Importantly, this is not simply barbarism. It is a case of poetic justice.

D. Adoni-Bezek Acknowledges God’s Justice (v. 7)

“Seventy kings with their thumbs and big toes cut off used to gather scraps under my table; as I have done, so God has repaid me.”

Adoni-Bezek's own confession validates the justice of his punishment. He becomes a living testimony to the lex talionis (“eye for an eye”), the principle of proportional justice. There is no indication that Israel acted cruelly—this is retributive justice in response to a cruel and godless oppressor.

What is most striking is that Adoni-Bezek himself acknowledges God:

“...so God has repaid me.”

Even this pagan king recognizes divine justice, offering a rare moment of insight in the midst of his downfall.

“Then they brought him to Jerusalem, and there he died.” — His final days were spent under Israelite custody in Jerusalem, a city not yet fully secured (cf. Judges 1:21). His death marks the end of a regional tyrant, and the beginning of Israel’s campaign to subdue the remaining strongholds.

Theological Insights and Applications

1. Unity Among God’s People Is a Prerequisite for Victory

The tribes did not operate in isolation; they cooperated in obedience to God's commission. Today, the Church must learn that spiritual victory is not a solo mission—it requires cooperative obedience, intercession, and faithfulness across the body.

2. Justice Is in God’s Hands

The fate of Adoni-Bezek is not revenge; it is justice. Even a pagan ruler testified, “God has repaid me.” His words mirror Galatians 6:7:

“Do not be deceived, God is not mocked; for whatever a man sows, that he will also reap.”

— Galatians 6:7, New King James Version

3. God Honors Obedient Boldness

Judah and Simeon went into hostile territory not assigned to them—but they fought in line with God's revealed will. This shows that faithful obedience may call believers to go beyond the borders of comfort or convenience, trusting that God has “delivered the land into their hands” (Judges 1:2).

4. Divine Mercy Amid Judgment

Even in a passage centered on judgment, we are reminded that God is not arbitrary. The punishment of Adoni-Bezek is not only just—it is recognized as just by the enemy himself. God’s justice always reveals His righteousness.

Summary of Judges 1:3–7

In this early episode, Judah and Simeon model faith, unity, and courage. God rewards their obedience with decisive victory. Adoni-Bezek, a cruel and powerful king, is captured and judged with the same cruelty he inflicted on others. His own testimony confirms that God’s justice is inescapable. This brief narrative is a vivid reminder that God is both righteous and present in the affairs of nations, and that His people are called to cooperate, trust, and conquer by faith.

Judah’s Victories and Incomplete Conquest in the South

Judges 1:8–20

Expositional Commentary

I. Conquest of Jerusalem and Southern Canaan (Judges 1:8–10)

“Now the children of Judah fought against Jerusalem and took it; they struck it with the edge of the sword and set the city on fire.”

— Judges 1:8, New King James Version

Judah’s campaign began with the attack on Jerusalem, the ancient Jebusite stronghold. Though they captured and burned the city, complete control was not maintained (see Judges 1:21). Later, during David’s reign—over 400 years later—Jerusalem was finally secured (2 Samuel 5:6–10). This initial victory, though incomplete, set a precedent that God's promises could be fulfilled through faith and obedience, even in the most fortified cities.

“And afterward the children of Judah went down to fight against the Canaanites who dwelt in the mountains, in the South, and in the lowland.”

— Judges 1:9, New King James Version

Judah's military campaign extended across three strategic regions:

The mountains (hill country between Jerusalem and Hebron),

The South (the Negev, a semi-arid region near Kadesh-Barnea),

The lowland (or Shephelah, the fertile foothills between the coast and the hill country).

This reflects a comprehensive attempt to secure the tribal inheritance granted in Joshua 15.

“Then Judah went against the Canaanites who dwelt in Hebron. (Now the name of Hebron was formerly Kirjath Arba.) And they killed Sheshai, Ahiman, and Talmai.”

— Judges 1:10, New King James Version

The slaughter of the sons of Anak, descendants of giants, was a significant spiritual and military milestone. These very giants had paralyzed Israel’s faith decades earlier (Numbers 13:22–33). Now, under faithful leadership, they were being driven out by Judah, led by Caleb (cf. Joshua 14:6–15).

II. The Conquest of Debir and the Faith of Caleb’s Family (Judges 1:11–15)

“From there they went against the inhabitants of Debir. (The name of Debir was formerly Kirjath Sepher.)”

— Judges 1:11, New King James Version

Debir, meaning "City of Books," may have been a center of Canaanite learning or idol worship. Taking this city would not only be militarily important but also symbolically valuable in subduing pagan influence.

“Then Caleb said, ‘Whoever attacks Kirjath Sepher and takes it, to him I will give my daughter Achsah as wife.’”

— Judges 1:12, New King James Version

Caleb offers his daughter Achsah in marriage as a reward for valor. This practice, while foreign to modern readers, was not uncommon in ancient cultures. It underscored the importance of military service to the tribe and family honor.

“And Othniel the son of Kenaz, Caleb’s younger brother, took it; so he gave him his daughter Achsah as wife.”

— Judges 1:13, New King James Version

Othniel—later Israel’s first judge (Judges 3:9)—proves himself to be a man of courage and initiative. His successful assault earned him the bride and affirmed his leadership. He was not only valiant in war but also honored within the faithful line of Judah.

“Now it happened, when she came to him, that she urged him to ask her father for a field. And she dismounted from her donkey, and Caleb said to her, ‘What do you wish?’ So she said to him, ‘Give me a blessing; since you have given me land in the South, give me also springs of water.’ And Caleb gave her the upper springs and the lower springs.”

— Judges 1:14–15, New King James Version

Achsah’s bold request is an example of faith-filled prayer and wise stewardship. She acknowledged her father’s blessing yet recognized the incompleteness of the inheritance without water—essential in the Negev’s arid climate.

This interaction is a parable of prayer. She knew:

What she needed (water),

Who could supply it (her father),

And how to ask (boldly, humbly, with gratitude).

Her petition reflects a theology of asking in faith (cf. Luke 11:13; James 1:5) and underscores that God's gifts are not begrudgingly given but graciously and abundantly supplied.

III. The Kenites and Additional Southern Victories (Judges 1:16–18)

“Now the children of the Kenite, Moses’ father-in-law, went up from the City of Palms with the children of Judah into the Wilderness of Judah…”

— Judges 1:16, New King James Version

The Kenites, descendants of Jethro, Moses’ father-in-law, are seen migrating with Judah. Though not ethnically Israelite, they align themselves with God’s people. This foreshadows the inclusion of Gentiles into God’s redemptive plan and shows the blessing of covenantal association with the righteous (cf. Ruth 1:16).

“And Judah went with his brother Simeon, and they attacked the Canaanites who inhabited Zephath, and utterly destroyed it.”

— Judges 1:17, New King James Version

This campaign culminates in the destruction of Zephath, renamed Hormah, meaning "devoted to destruction." It recalls the earlier failed attempt at Hormah in Numbers 14:45 and now vindicates Israel’s obedience through Judah.

“Also Judah took Gaza... Ashkelon... and Ekron with their territory.”

— Judges 1:18, New King James Version

These were key Philistine cities. Though Judah captured them, Israel failed to maintain control long-term. These cities later become persistent thorns to Israel, especially in the days of Samson and Samuel.

IV. Incomplete Conquest Due to Iron Chariots (Judges 1:19–20)

“So the LORD was with Judah. And they drove out the mountaineers, but they could not drive out the inhabitants of the lowland, because they had chariots of iron.”

— Judges 1:19, New King James Version

This verse reveals the limit of Judah’s faith, not God’s power. Iron chariots were no match for God (see Exodus 14:7–29; Joshua 11:6–9). The real problem was spiritual—fear and unbelief, not military deficiency.

“Some trust in chariots, and some in horses; but we will remember the name of the LORD our God.”

— Psalm 20:7, New King James Version

“And they gave Hebron to Caleb, as Moses had said. Then he expelled from there the three sons of Anak.”

— Judges 1:20, New King James Version

Caleb, a man of unwavering faith, defeats the giant Anakim, where others faltered. His example proves that victory comes through trusting in the promises of God, not in military advantage or human strength.

Theological and Practical Application

Victory requires full obedience. Partial conquest leads to long-term bondage. Judah’s early victories are commendable, but the failure to press forward in faith leads to compromise and consequences.

God is not hindered by iron chariots. His promises require courage, not perfect circumstances. If Judah had trusted Him fully, they would have conquered both hill and valley.

Faith is generational. Caleb’s courage and Othniel’s boldness reflect a heritage of spiritual strength. Teach and cultivate this in families today.

True blessings require more than land. Achsah knew that without water, her inheritance was barren. So too, without the living water of the Holy Spirit, no ministry or possession has power or fruit.

Prayer should be bold and specific. Achsah’s request shows that God honors those who approach Him with confident dependence and clear understanding of their need.

B. Incomplete Victory and Defeat

Judges 1:21–29

Expositional Commentary

1. Benjamin Fails to Take Full Possession of Jerusalem (Judges 1:21)

“But the children of Benjamin did not drive out the Jebusites who inhabited Jerusalem; so the Jebusites dwell with the children of Benjamin in Jerusalem to this day.”

— Judges 1:21, New King James Version

This verse is a direct indictment against partial obedience. Though Judah initially captured Jerusalem (Judges 1:8), the tribe of Benjamin failed to drive out the Jebusites who remained entrenched. As a result, Jerusalem remained a divided stronghold, with both Israelites and Jebusites dwelling in it until the time of David (2 Samuel 5:6–10).

This was not a failure of opportunity, but of resolve and follow-through. The military battle had already been won; the land had been granted; only faith-fueled obedience was required. Their refusal or inability to finish the job introduced spiritual compromise and cohabitation with idolatry at the heart of Israel’s territory.

This failure teaches a crucial spiritual truth:

What is not driven out will eventually dominate.

2. Joseph’s House Conquers Bethel (Judges 1:22–26)

“And the house of Joseph also went up against Bethel, and the LORD was with them.”

— Judges 1:22, New King James Version

In contrast to Benjamin’s failure, the house of Joseph—representing Ephraim and Manasseh—sought the LORD and experienced success. Bethel (“House of God”) held patriarchal significance (Genesis 28:19) and spiritual symbolism. Their approach was both strategic and divinely blessed.

“So the house of Joseph sent men to spy out Bethel... So he showed them the entrance to the city, and they struck the city with the edge of the sword...”

— Judges 1:23–25, New King James Version

This mirrors the conquest of Jericho (Joshua 2, 6), where Rahab assisted the Israelite spies. Here, an unnamed man bargains for his life and helps them enter the city. While the LORD was with them, this mercy extended to the man and his family shows that God’s judgment is never without room for repentance.

“And the man went to the land of the Hittites, built a city, and called its name Luz...”

— Judges 1:26, New King James Version

The man rebuilds Luz, symbolizing that human compromise and paganism often find new ground when not wholly uprooted. This is a picture of sin finding fresh soil when not dealt with thoroughly.

3. Manasseh and Ephraim’s Failure to Fully Obey (Judges 1:27–29)

“However, Manasseh did not drive out the inhabitants of Beth Shean… Taanach… Dor… Ibleam… Megiddo… for the Canaanites were determined to dwell in that land.”

— Judges 1:27, New King James Version

The tribe of Manasseh, though strong and numerous, compromised. The text clearly states that the Canaanites were determined—but that only underscores the need for faith and divine dependence, not surrender. God had already promised victory if Israel remained obedient (cf. Deuteronomy 7:1–6).

“And it came to pass, when Israel was strong, that they put the Canaanites under tribute, but did not completely drive them out.”

— Judges 1:28, New King James Version

This statement reveals a deadly rationalization: strength was used not for obedience, but for economic exploitation. They thought tribute (forced labor or taxation) was more profitable than obedience to God’s command to purge the land. This compromise would eventually ensnare their hearts and corrupt their worship.

“Nor did Ephraim drive out the Canaanites who dwelt in Gezer...”

— Judges 1:29, New King James Version

This failure mirrored that of Manasseh. In fact, Gezer would not come under full Israelite control until the time of Solomon, when Pharaoh gave it to his daughter (1 Kings 9:16). Israel’s failure to trust God for the immediate removal of the enemy delayed full possession of the land for generations.

Doctrinal and Practical Lessons

1. Partial obedience is total disobedience in the eyes of God.

Israel’s compromise wasn’t neutral—it was rebellion. Obedience is not just about starting with zeal but about finishing with faith.

2. Strength without submission becomes pride.

When Israel became strong, instead of finishing the conquest, they used their strength for gain. Power used outside of God’s will always corrupts.

3. Canaanites in the land represent sin in the life.

Every believer faces the temptation to allow "small sins" to remain. But these footholds of compromise will become strongholds of rebellion unless completely driven out (Romans 6:12; Hebrews 12:1).

4. God values purity over pragmatism.

Israel saw tribute as beneficial. But God saw cohabitation with Canaanites as defilement. Economic or political gain must never trump obedience to Scripture.

Conclusion: The Slow Fade Begins

Judges 1 begins with promise and early triumphs, but by verse 29, the tone shifts toward compromise and creeping failure. The tragic irony is that Israel, after showing strength, stopped short of full obedience—not because they couldn’t finish the job, but because they chose not to.

As G. Campbell Morgan said,

“God is perpetually at war with sin. That is the whole explanation of the extermination of the Canaanites.”

Israel’s neglect to drive out the enemy was not just military failure—it was spiritual treason, and it set the stage for the national apostasy that dominates the rest of the book.

Incomplete Victory and Defeat

Judges 1:30–33

Expositional Commentary

4. Zebulun Compromises Through Partial Obedience (Judges 1:30)

“Nor did Zebulun drive out the inhabitants of Kitron or the inhabitants of Nahalol; so the Canaanites dwelt among them, and were put under tribute.”

— Judges 1:30, New King James Version

The tribe of Zebulun, located in the northern hill country near Galilee, failed to expel the inhabitants of Kitron and Nahalol, contrary to God's direct command (Deuteronomy 7:1–5).

This was not simply a missed military objective; it was a failure to act in faith and obedience. The land had been promised, the victory assured—but it still required full surrender to God’s command to purge idolatry and opposition.

“So the Canaanites dwelt among them, and were put under tribute.” — Zebulun followed the same pattern of compromise already seen in Manasseh and Ephraim. Rather than destroy the Canaanites, they subjected them to forced labor or taxation, believing economic benefit justified spiritual compromise.

Key Insight:

What seems economically profitable today becomes spiritually enslaving tomorrow.

This arrangement fostered social assimilation, leading to idolatry, intermarriage, and spiritual dilution. The crisis did not erupt immediately, but the seeds were planted—and would bear corrupt fruit in later generations.

5. Asher Entirely Fails to Possess Its Inheritance (Judges 1:31–32)

“Nor did Asher drive out the inhabitants of Acco or the inhabitants of Sidon, or of Ahlab, Achzib, Helbah, Aphik, or Rehob. So the Asherites dwelt among the Canaanites, the inhabitants of the land; for they did not drive them out.”

— Judges 1:31–32, New King James Version

Asher’s failure was more severe than Zebulun’s. Instead of allowing the Canaanites to live among them, it was the Asherites who lived among the Canaanites—a spiritual reversal of God's plan.

God intended for His people to be the dominant influence in the land—cleansing it of idolatry, establishing covenantal worship, and forming a holy society. Instead, Asher surrendered their calling and identity, choosing to dwell within the pagan culture they were commanded to conquer.

Doctrinal Principle:

When God’s people refuse to stand apart, they will inevitably be pulled in.

The coastal cities listed—Acco, Sidon, Achzib, etc.—were centers of Phoenician trade, Baal worship, and pagan culture. Asher’s accommodation of such cities would later impact Israel’s spiritual fidelity, particularly in the northern kingdom’s apostasy under Ahab and Jezebel.

“They did not drive them out…” — No mention of military defeat is given here—only spiritual passivity. The sin here is not inability, but unwillingness.

6. Naphtali’s Compromise and Dual Capitulation (Judges 1:33)

“Nor did Naphtali drive out the inhabitants of Beth Shemesh or the inhabitants of Beth Anath; but they dwelt among the Canaanites, the inhabitants of the land. Nevertheless the inhabitants of Beth Shemesh and Beth Anath were put under tribute to them.”

— Judges 1:33, New King James Version

Naphtali followed the path of Zebulun and Asher, both dwelling among the Canaanites and subjecting some to tribute. This represents a dangerous double compromise:

Social compromise: Allowing pagans to coexist with them.

Spiritual compromise: Leveraging them for profit rather than removing them for purity.

The cities Beth Shemesh ("house of the sun") and Beth Anath were named after pagan deities—Sun worship and goddess worship—yet Naphtali chose to live under that spiritual shadow rather than fight.

“Nevertheless... were put under tribute.” — Again, economics trumped theology. This was not the slow, divinely guided conquest described in Exodus 23:29–30 or Deuteronomy 7:22–24, where God gives the land little by little to test Israel’s faith. This was willful inaction and self-serving settlement.

Theological Implications

1. One Tribe’s Compromise Weakens the Whole Nation

When one tribe disobeyed, others followed. Compromise spreads faster than courage. Zebulun’s half-measures emboldened Asher’s passivity, which in turn made Naphtali's surrender seem justifiable.

“A little leaven leavens the whole lump.”

— Galatians 5:9, New King James Version

2. Delayed Judgment Does Not Equal Divine Approval

The fact that the crisis was not immediate gave Israel a false sense of security. But as the rest of Judges reveals, the consequences were inevitable—spiritual apostasy, national fragmentation, and God’s chastening hand.

3. Partial obedience is fertile soil for idolatry

The decision to let Canaanites live among them allowed for intermarriage, idol worship, and cultural corruption. The future sins of Israel began right here in these overlooked failures.

Practical Applications

Don’t make peace with besetting sin — The modern believer must learn from these tribes: what you do not crucify, will control you.

Faith requires perseverance — God intended the conquest to be gradual to build Israel’s faith (Deuteronomy 7:22), but they grew weary. Faith that starts well must also finish well (Hebrews 12:1–2).

Don’t measure success by earthly standards — Israel thought tribute equaled victory. But God measures success by obedience, not by income, efficiency, or comfort.

Conclusion: The Drift into Darkness

Zebulun, Asher, and Naphtali reveal a descent from partial obedience to complete passivity. These verses form a theological commentary on how nations fall—not with one cataclysm, but by a series of small compromises. They begin with incomplete obedience, slide into comfortable disobedience, and end with spiritual collapse.

“If we can’t have it easy, then we don’t want it at all.”

That was their unspoken attitude—and it is ours too, if we are not watchful.

7. Dan’s Failure and the Enemy's Encroachment

Judges 1:34–36

Expositional Commentary

Text: Judges 1:34–36

“And the Amorites forced the children of Dan into the mountains, for they would not allow them to come down to the valley; and the Amorites were determined to dwell in Mount Heres, in Aijalon, and in Shaalbim; yet when the strength of the house of Joseph became greater, they were put under tribute. Now the boundary of the Amorites was from the Ascent of Akrabbim, from Sela, and upward.”

— Judges 1:34–36, New King James Version

A. The Tribe of Dan Driven Back (v. 34)

“The Amorites forced the children of Dan into the mountains…”

The failure of Dan is unique because it wasn’t merely passive compromise or failure to finish. This was active defeat. Rather than driving out the Amorites, Dan was driven back—not because God’s promises failed, but because Dan failed to trust and obey.

This was a complete reversal of covenant expectation. Israel had been promised dominion over the land (Deuteronomy 11:23–25), but here, they are subjugated. The enemy dictated boundaries, geography, and settlement.

“For they would not allow them to come down to the valley…”

Dan was effectively pinned in the mountains, cut off from the fertile and strategic lowlands. This speaks volumes spiritually: when God’s people surrender ground through fear or compromise, they are confined to fruitless territory, unable to fulfill their calling or enjoy the full inheritance.

B. Amorite Determination vs. Israelite Weakness (v. 35)

“The Amorites were determined to dwell…”

The spiritual war is not passive. The enemy is resolute, even when the people of God are not. This verse contrasts the determination of Israel’s enemies with the capitulation of God’s people. What should have been a conflict won by divine power became a stalemate because Israel ceased striving in faith.

“Yet when the strength of the house of Joseph became greater, they were put under tribute.”

This follows the same failed pattern we’ve seen with other tribes (Manasseh, Ephraim, Zebulun, Naphtali): economic exploitation instead of total obedience. The house of Joseph—strong militarily—chose tribute over total expulsion, seeking profit over purity.

As Matthew Henry noted, “They thought themselves wiser than God, and fitter to manage His enemies than He Himself was.”

C. The Amorite Boundary Established (v. 36)

“Now the boundary of the Amorites was from the Ascent of Akrabbim, from Sela, and upward.”

Rather than Israel establishing national boundaries, the Amorites are granted their own territory—within what should have been Israel’s inheritance.

This is the ultimate failure: the enemy sets the terms of coexistence. Israel had not just failed militarily—they had ceded spiritual authority in the land. What should have been holy ground for Yahweh became divided, polluted, and permanently compromised.

Doctrinal and Theological Implications

1. Spiritual Warfare Cannot Be Avoided

The tribe of Dan illustrates a crucial spiritual reality: you cannot negotiate with the enemy. Ephesians 6:11–13 makes clear that believers must put on the whole armor of God. To avoid the conflict is to forfeit territory and calling.

“Put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil.”

— Ephesians 6:11, New King James Version

The Amorites didn’t offer peace; they pushed. And Dan backed down.

2. Fear of the Enemy Is Unfaithfulness Toward God

The narrative does not say the Amorites were invincible, only that Dan was pushed into the mountains. This was not about tactical disadvantage; it was about spiritual retreat. The God who split the Red Sea and stopped the sun for Joshua had not changed. The people had.

“Have I not commanded you? Be strong and of good courage… for the LORD your God is with you wherever you go.”

— Joshua 1:9, New King James Version

Dan lacked this courage, and thus, they lost their inheritance.

3. Tribute Is Not a Substitute for Obedience

Once again, Israel opted for tribute over conquest. The short-term gain of wealth blinded them to the long-term cost of corruption. God had not commanded them to tolerate the Amorites; He had called them to expel them (Deuteronomy 7:1–2).

“This they did out of covetousness, that root of all evil.”

— (John Trapp)

Practical Applications for Believers

Do not let your enemy define your boundaries. Many Christians live in spiritual retreat, allowing past sins, fears, or fleshly strongholds to dictate their freedom. If we allow strongholds to remain unchallenged, they will claim what God has given us to conquer.

Beware of the pacifism of convenience. There is a seductive belief that says, “If I don’t resist sin too strongly, maybe it won’t attack me.” This is a lie. Sin, like the Amorites, is determined to dwell—and if not cast out, it will rule.

The victory of Christ is complete—ours must be consistent. Jesus Christ finished the work of salvation entirely (John 19:30), but the application of His victory in our lives must be worked out through obedience, repentance, and spiritual warfare (Philippians 2:12–13).

Conclusion: Dan’s Defeat Foreshadows National Apostasy

The failure of Dan marks a tragic descent from spiritual apathy to full surrender. Whereas Judah had early victories, Dan ends the chapter in displacement and subjugation. This sets the stage for a key theme in Judges: when God’s people fail to walk in His promises, they inevitably live beneath their privilege, power, and purpose.

What Israel could not finish, Christ has already completed. As believers, we are called not to seek comfort in coexistence with sin, but to pursue holiness through warfare, obedience, and trust in the sufficiency of Christ.

“Thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.”

— 1 Corinthians 15:57, New King James Version